“There is, one knows not what sweet mystery about the sea, whose gently awful stirrings seem to speak of some hidden soul beneath.” Herman Melville

That being said, making an ocean passage in a sailboat is easily the most ridiculously crazy, intensely uplifting, completely terrifying, yet amazingly satisfying thing I have ever done. This is our third crossing through different sections of the North Atlantic and yet each has been truly unique. It is much like comparing three children from the same family. They all are born of the same parents, have the same genetic makeup, yet each looks different from the other, has different emotions, reactions, and attitudes toward life. You may have crossed one part of an ocean, but a new section will leave you breathless with the variations and differences.

Just before departing the Azores to make our crossing to mainland Europe, we had the privilege of meeting Jonathan and Anne Lloyd from the sailing vessel Sofia. Sofia had departed a few days before we got to the island of Terceira but we didn’t get a chance to meet them before the first time they set sail. Unfortunately, as unpredictability can certainly be predicted, 80 miles into their voyage they encountered a very aggressive electrical storm. Taking precautions, they put their phones, handheld VHF, and Epirb (emergency hailing unit) into their microwave oven in case of a lightning strike making contact with their boat. The unfortunate occurred. A bolt of lightning struck their mast, instantly taking out all the boat’s electronic systems.

I always say that we have an extra bit of luck with us on this world sailing adventure. The day after we officially raised our OCC flag in the Marina da Praia da Vitoria, Azores, a gentleman greeted us and welcomed us to the OCC. What are the chances of meeting a commodore in person, the day after we were accepted into the organization? While Sofia began her emergency repairs at the same marina, Johnathon walked the docks looking for OCC members. He invited us to an impromptu meeting being held the following evening at a bar in the marina.

One of our challenges, as we sail to new parts of the world, is wondering where to go, what we will encounter, and the best places to bring our boat. Heading to the UK had us wondering where to make landfall, the best ports to visit, and what to expect in general. Wouldn’t you know that during our first OCC meeting, after we were officially welcomed and met the group, we were introduced to sailors from England, Ireland, Scotland, and Finland. These are the first countries we will be exploring in the UK. Our new friends each took time during the evening to give us their contact information, offer suggestions, and provide just the kind of information we had been seeking. Our level of comfort approaching the UK instantly increased.

Our friends on Rockhopper experienced that phenomenon first hand on their way to the Azores. Before they left Bermuda, they heard rumors of a boat owner and 3 crew members looking for someone who would take them to their 50 ft. sailboat floating adrift in the Atlantic. It was intact, abandoned after having rudder failure, and floating around still emitting a GPS signal. They had been sailing to the Azores when the boat’s rudder broke. A temporary tiller had been installed but with the onset of severe weather, the captain and crew signaled for rescue and abandoned ship.

Jonathan also relayed a story to me about his experience as a 10-year-old, over fifty years ago, when sailing was done by hand and there were no electronics for navigation or sophisticated weather services. His father had taken him from England over to Ireland on their family sailboat. They arrived in the harbor at sunset and all was quiet and calm. They anchored with only one other boat in the harbor, the rescue boat for the local emergency response people. By the next day, the Atlantic changed her mood as women can quickly do, and she went from calm and placid to raging and furious. He described looking out and seeing 50 ft. crashing rollers entering the harbor. While his father remained calm at first, he began to despair when their wooden dinghy broke free and they watched it crash to pieces on the rocky shore.

Deciding their vessel was in peril, their anchor showing sign of losing its grip, Jonathan’s father lit two emergency flairs in the midst of the raging chaos. Within moments, they spotted men along the shore holding up signal flags. They weren’t quite sure what the men were saying, but they did know help was on the way. Before long, a whaleboat filled with men appeared on the tumultuous horizon. It would appear, then disappear amidst the troughs of the mountainous waves. The men had no oars or sail, just one individual fiercely gripping the tiller. They were completely at the disposal of the waves and had no other way to propel themselves than to ride the 50 ft. waves toward the boat in distress.

The men in front were armed with a grappling hook. The goal was to get to the rescue boat, and as they passed, launch the hook and then get themselves aboard their boat with a 1,000 hp engine for the rescue. They had one chance as they rocketed by. If they missed, they would crash upon the rocky shore and suffer the same fate as the dinghy. Carefully, and with great skill, the men surfed the whaleboat over and across the massive rollers and hooked their boat on the first cast of the line. They immediately sprang into action, pulled up the anchor and came to rescue Jonathan and his father.

Having heard this story and several others from Jonathan, I suddenly understood why he remained so confident and unperplexed about his lightning strike experience. While it was unfortunate, it wasn’t life-threatening and certainly repairable. He also brought up a good point about being an OCC member. He told me that whatever part of the world you are in if you need help or assistance, you will find an OCC member. It was clear this was an organization that provided support and friendship between a unique group of people with the common goal of voyaging across oceans. It was comforting as we made our preparations to depart to the UK the following day.

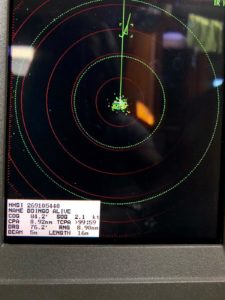

We plotted and studied the weather patterns for the upcoming week. Chris Parker is a professional weather router that offers weather reports and customized predictions for those making ocean passages. Based on his reports and our research using 3 different weather models, three of us set to cross to Europe, Sophia, Rockhopper, and Equus. Out at sea, we have two options for looking at weather daily, downloading our grib files through our satellite phone or listening to Chris Parker on our SSB, single sideband radio. We also choose a time each day to talk to one another on the SSB to make sure everyone is safe and get a position report. We may be spread 80 to 100 miles apart, but we can still communicate and share info and resources.

Testimony to rigors of this motion is the fact that anything not securely tied down instantly becomes a projectile. Our goal is to not become like those objects and strive to move, sit, stand, or use the bathroom, without flying across the cabin. My greatest challenge is preparing meals. Every item you put out makes it its goal to evacuate the countertop the second you take your hand away. The trick is controlling all the ingredients for a meal while making sure the food, plates, bowls, and utensils don’t leave the counter. We’ve had our share of spilled drinks, food on the floor, and other food disasters, but the worst of all was The Great Spaghetti Disaster.

Almost all my meals were prepared in advance so all I had to do was heat them up. I had a few cooked hamburger patties leftover I needed to use up and I was in the mood for spaghetti. While the boat was rocking a bit heavily, I felt I was up for the challenge. I needed to find a jar of spaghetti sauce in my pantry and set to the task of digging one out. I opened the cabinet door just as the boat rocked heavily to one side, of course, it was toward the open side of the pantry door. About a dozen cans and jars jettisoned themselves out the escape hatch. They were like tiny paratroopers fleeing from an airplane and they all had different routes in mind. I had my arm deep in the cabinet, latched to a jar of sauce when all hell broke loose. I yelled to Dan for backup and he quickly came to the rescue.

My mistake was putting the jar of sauce down to try and grab some of the other escaped items. Cans of beans, corn, and soup, rolled around the floor as Dan and I tried our best to corral them. We systematically stuffed them back in the cabinet. I realized then, the jar of sauce was missing. It has scurried across the cabin so I took off after it on all fours. Just then, a big wave hit the side of the boat and all momentum shifted. I chose self-preservation over the sauce and held on to the companionway stairs while watching the sauce pass back by me and roll under the salon table. Needless to say, the chase ensued but finally, I rose, sauce in hand, victorious. But that was just the beginning. I hadn’t even begun to cook yet.

I wanted to use some of my fresh veggies in the sauce, onions, peppers, zucchini, fry them up and add them to the already cooked hamburger. I tried putting them all on the counter at once, but after each one rolled off in a different direction, I changed tactics and dealt with one at a time. Meanwhile, I had water on the back burner boiling for the pasta. I was a little trepidatious about working with boiling water on a rolling platform, but I vowed to be extra cautious. My sauce was finally complete, the pasta ready. I had a strainer in the sink to pour the hot water and pasta into. I braced myself and carefully carried the boiling water over to the sink. Don’t you know, that’s when another big wave hit. I poured the water and pasta into the sink but totally missed the strainer. Good thing I had just cleaned my sink as I had to scoop the scalding pasta back into the strainer.

Everything finally under control, I pulled out the plates and utensils. The utensils left immediately. I retrieved them and put them back in the drawer. As I did that, the plates launched off the counter. Strike two. Refusing defeat, I got a rubberized mat and put the plates on it. I watched for a few seconds. The boat rocked. The plates stayed intact. “YES!” I thought to myself. “This will work.”

I piled even amounts of spaghetti noodles on each plate. Good so far. Then, I heaped my sauce onto each mound. The aroma was tantalizing and I craved a belly full of the meal I had worked to hard to prepare. Satisfied all was well, I opened the drawer and retrieved the utensils. Dan was seated at the table so I brought over the forks and some napkins. I set them on the table smiling with anticipation of our dinner. Suddenly, I noticed the expression on Dan’s face. It was like a scene from a movie played in slow motion. I watched in horror as his mouth form the word, “NOOOOOOOO!”

I wheeled around but it was too late. My plates were still firmly in place on the mat, but the spaghetti apparently didn’t get the “stay put” memo. My counter was now covered in red sauce and noodles, seeping into every crevice, into the storage compartment under that counter, and just about everywhere else it could venture. My dinner had turned into a disaster.

Fair winds and following seas…

Dan and Alison

S/V Equus